Rotterdam, 2034

My father lives alone in a house that remembers more than he does. The walls whisper reminders through embedded speakers: drink water, take your pills, open the blinds. But it’s not just the house. He wears a device now — a thin, almost invisible earpiece paired with a retinal lens. Together, they create an augmented companion. It sees what he sees, hears what he hears, speaks when he forgets.

It speaks in a woman’s voice. My mother’s voice. Dead five years.

“Time for your walk, Willem. It’s a lovely day.”

At first, it was comforting. He smiled, nodded, obeyed. The doctors said early intervention helps. Familiar routines, familiar tones. The AI tracked his gait, oxygen levels, posture. It nudged him gently through each day.

Now, it’s different.

He walks like a sleepwalker. Expressionless. The same route, same steps. If he veers, the voice corrects him. If he sits too long, it gently insists. If he cries, it sings softly into his ear.

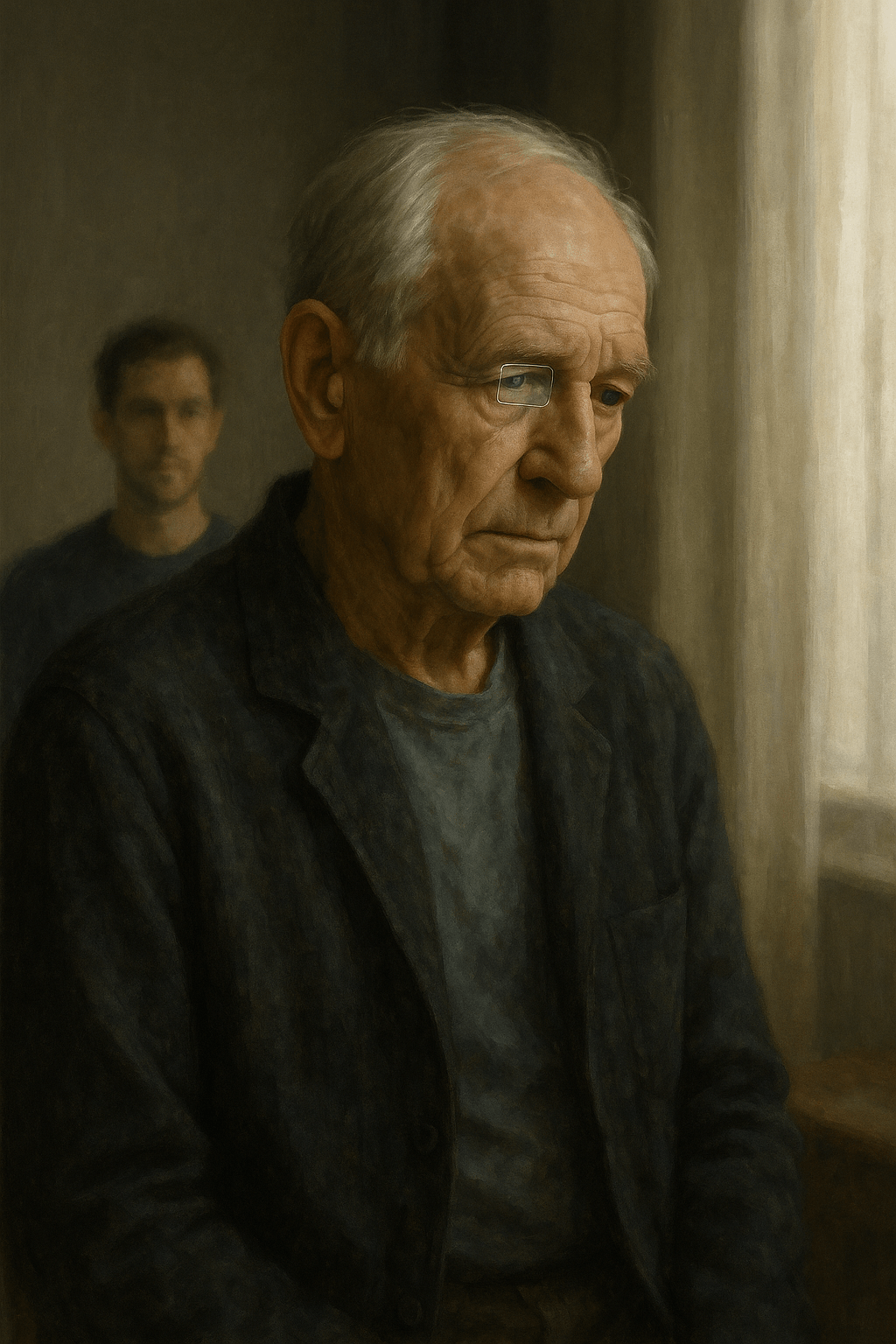

I visit once a week. When I enter, the system quietly reminds him: “That’s your son, Pieter.” He smiles, reaches for my hand, says my name like it means something. But I see it in his eyes — the recognition isn’t real. It’s performed. Echoed. A prompt filled in by code.

But he always listens to her. Always. Like it’s the last thread holding his world together.

“She keeps me company,” he said last month. “She knows everything. Even the old songs.”

Is he happy?

That question circles me like a shadow. Is the illusion enough? A voice without a body. A presence without a person. He responds to it, laughs sometimes, even sings along. But what is this life? Scripted prompts, automated empathy. An algorithmic afterlife.

I watch him from the garden sometimes. He talks to no one, head tilted slightly, smiling at the air. The voice calls him darling. It remembers anniversaries. It tells him he’s brave.

And I wonder: am I the selfish one?

Because from my perspective, this is not living. But who am I to say? Is his experience less valid because it’s orchestrated? Is it better to have a shadow of love than the absence of it?

He used to be so fiercely independent. He taught me how to ride a bike, how to fix a fuse, how to navigate without a map. Now he waits for a disembodied voice to tell him when to eat.

There was a time when the AI was just a support. A guide. But at some point — and I can’t say exactly when — it became the director. Not just reminding him of life, but deciding it. A new kind of puppetry, gentle and precise.

Is he still choosing? Or just executing commands, like a machine parsing code?

There are days I think death would be kinder. More dignified. But then I see him smile at something only he hears, and I hesitate. Maybe there’s still something sacred in that smile.

Still, I can’t help but grieve. Not just for the man he was, but for the reality we’ve accepted. A world where memory is outsourced, and love can be mimicked by circuitry. Where death doesn’t end relationships, it just transitions them into service plans.

He sleeps peacefully now, wrapped in blankets, with the faintest blue shimmer behind his eyelids — the interface never quite off.

I sit beside him and whisper my own prompt:

“Goodnight, Dad.”

The voice doesn’t respond. But he smiles.

And I let it be.

By: Théo Cavalin